In our recent tune “Messenger” we paid tribute to the late Wayne Shorter. In addition to his work as a saxophonist, both as a band leader and a sideman with artists ranging from the Jazz Messengers and Miles Davis to Steely Dan and Don Henley, Shorter was known as an influential jazz composer. One characteristic of his writing was his use of non-functional harmony.

What exactly is non-functional harmony? Perhaps it can be more easily defined by what it isn’t. Non-functional harmony is different from atonality in that it still often features familiar major and minor chords and can have a key center, but the harmonic movement does not follow typical patterns. If atonal music might be compared to abstract art, music with non-functional harmony could be compared to impressionism. According to www.beyondmusictheory.org, non-functional harmony “occurs when no chord ‘wants’ to specifically resolve to the next one…more often than not, the goal is to evoke a mood, feeling or atmosphere…” As this article from Berklee Today points out, creating non-functional harmony is “not so much deciding which techniques to use…but which ones to avoid. Functional harmonic patterns (like II-V-I patterns, dominant to tonic resolutions, circle of fifths sequences, and line clichés) contribute to harmonic predictability and set up expectations in standard tunes.”

Indeed, traditional jazz standards often used II-V-I cadences and other established harmonic building blocks. Many early be-bop staples were reworkings of older tunes, such as Charlie Parker’s “Ornithology”, which used the same chord progression as “How High the Moon.” Some tunes, including “Joy Spring” by Clifford Brown and “Airegin” by Sonny Rollins, had progressions that were more intricate than those of the Great American Songbook era, but still followed similar patterns.

However, following Miles Davis’s “Kind of Blue”, jazz musicians started to break away from the status quo. In the 1960s, Wayne Shorter left his mark on the jazz canon with “Ju-Ju”, “Speak No Evil”,“Virgo” and other tunes which explored new harmonic territory. His boundary-stretching as a composer continued into the 1970s with Weather Report and subsequent solo albums such as “Native Dancer” and “Atlantis.” His compositions were praised for being unpredictable while, thanks to his melodic and rhythmic sensibilities and deliberate chord choices, also accessible to a wide audience.

Composers and songwriters in jazz and other genres looking to break out of common chord progressions might find inspiration in the non-functional harmonies of Shorter and his contemporaries. In the following three examples, we will look at how Wayne Shorter uses non-functional harmonies to create unpredictable tunes while also using traditional techniques such as motivic development to maintain a sense of structure and continuity.

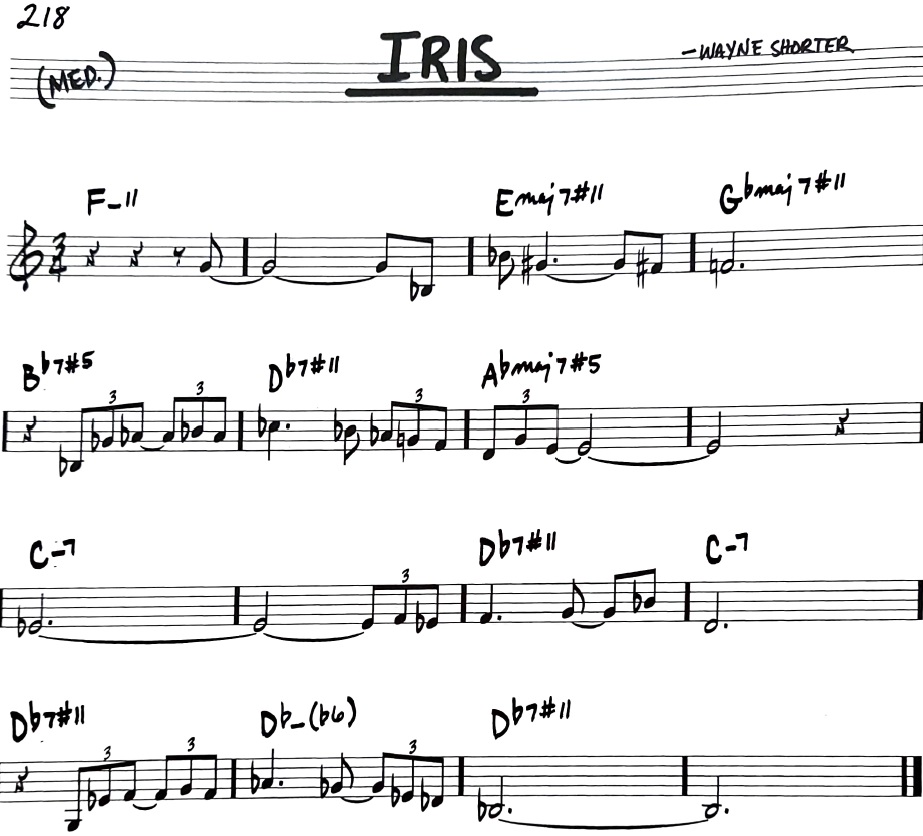

The harmonies of “Iris” (1965) have roots in the modal jazz of “Kind of Blue”; the half step movement from Cm7 to Db7 back to Cm7 in bars 9 to 12 recall “So What.” However, while the harmonic rhythm of “Iris” maintains the leisurely pace of modal jazz (no chord is held for less than a full measure and four chords are held for two measures), the movement of the chords is less predictable. The Fm11 of the first two bars seems to establish a tonality, only to move to Emaj7 in the third bar and Gbmaj7 in the fourth. The sparse melody enables the listener to digest these changes; though the harmonic movement is not what we expect, the overall effect is not jarring. Bars 5 to 8 introduce a contrast, both in the activity of the melody and in the chord quality: we have two consecutive altered 7th chords, providing variety from the major and minor 7ths of the first phrase. While not a resolution in the traditional sense, the Abmaj7#5 of 7-8 feels like a pause after the prior two busy measures, even with the tension of the E natural in the melody. In the second half of the tune, the melody echoes that of the first half, providing some continuity over the new chords. In the last line, Shorter creates harmonic ambiguity by alternating between dominant 7th and minor chords in a way that is rarely seen in more traditional chord progressions.

In “El Gaucho” (1966), Shorter uses a recurring melodic motif to bring unity to a non-functional chord progression. In the second measure, the motif is repeated higher than in the first, while the harmony moves lower (F to Eb). In the third measure, the motif appears in its original register over a different chord (D minor). The fourth measure appears to be setting up a move to an A tonality (B7 to E7 as a II7-V7), but instead of the expected resolution, the harmony moves back to F, this time minor. By returning to the original tonality via an unexpected route, Shorter employs non-functional harmony in a way that still fits the structure of the tune. Variations of the four-note motif continue over different chords: Gbmaj7 in measures 6 and 8; Dm7 in measures 12 and 14.

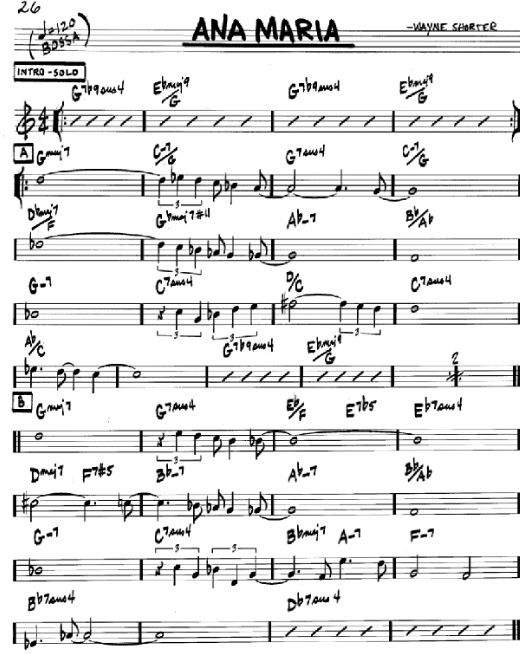

“Ana Maria” (1975) starts with a progression based around a G pedal. Shorter seems to be building tension that will release to a C tonality (the traditional V-I movement), but he remains in G when the main tune begins. A variation on the first motif is heard over a new tonality in the fifth bar of the “A” section. In the ninth bar, the G tonality returns, now minor. The “B” section begins in the same way as the “A” (Gmaj7) before varying both the melody and harmonies. Because the change in the melody is subtle (E descending to Bb, compared to Eb descending to A), Shorter is able to make a more dramatic change in the harmonies: instead of the G pedal, the bass notes now move downward chromatically, arriving at a Dmaj7 chord in the fifth bar of the “B” section. However, after this variation, the next three bars are the same as the corresponding three in the “A” section. Bar 10 of “B” begins in the same manner as its “A” counterpart before diverging again, moving to Bbmaj7, Am7 and Fm7. We see again how, while the chords don’t follow traditional patterns, they don’t feel chaotic thanks to Shorter’s use of recurring motifs and strategic decisions about when and where to move tonalities.

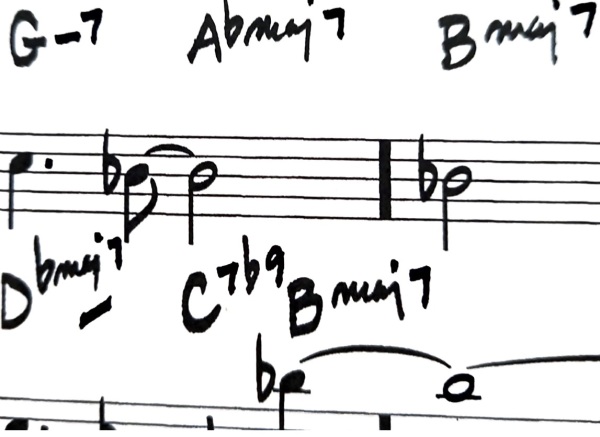

The opening of our tribute tune “Messenger” uses non-functional harmony inspired by Shorter. The bass line is a tetrachord: D-E-F-G while the triads placed on top of these notes, C, B, Eb and F, don’t fit together in a traditional way. The second measure features another tetrachord in the bass: A-B-C-Db, with more new chords on top: E-F#-D-Ab. However, the chords are played in the same rhythm, serving as a common thread.

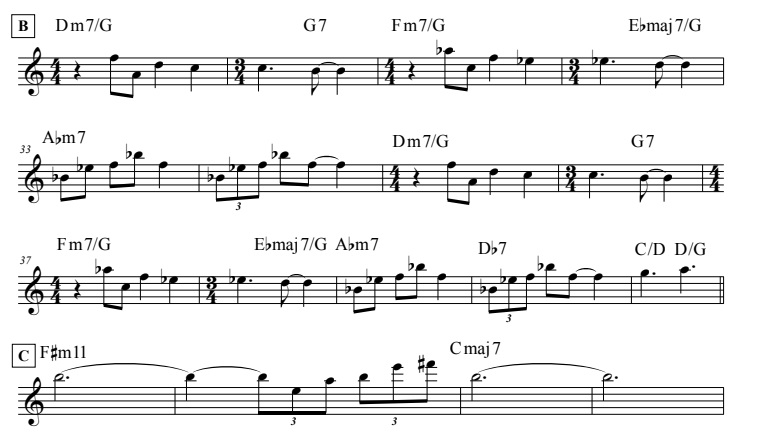

Since the introduction is busy, a slower harmonic rhythm in the “A” section creates variety. The first two chords, F#m11 and Cmaj7, are not related, but are tied together by the melody note of B. After leaving the Cmaj7 chord, the root motion ascends: D – Eb – F, setting up a return to F#m11 in bar 13. However, the chords then diverge from the previous “A” section, with the root motion climbing: G#, A, B. Bars 5 to 11 are repeated verbatim from 21 to 27, but a new chord – F#dim7 at measure 28 – sets up the “B” section.

This section is built around pedal points – first G, then Ab – which contrast the movement of the harmonies, starting out in D minor, moving by minor thirds to F minor and then Ab minor. At measure 39, there is a hint of a ii-V-I progression, with Abm7 and Db7 breaking away from the stepwise root motion that has been common up to this point. The progression eventually will resolve, but not in an expected way: two non-functional hybrid chords in bar 41 (C/D and D/G) create uncertainty before the return of the original theme at “C”. Without measure 41, the root motion would resemble a ii-V-I, but it would still be somewhat unconventional in that the I is minor and the enharmonic equivalent (F# rather than Gb).

If Wayne Shorter had been just a saxophonist or just a composer, he still would have been remembered as a major figure of post-bebop jazz. As both, he left a body of work that will be enjoyed and studied as it continues to influence musical generations to come.